Engineers and boredom

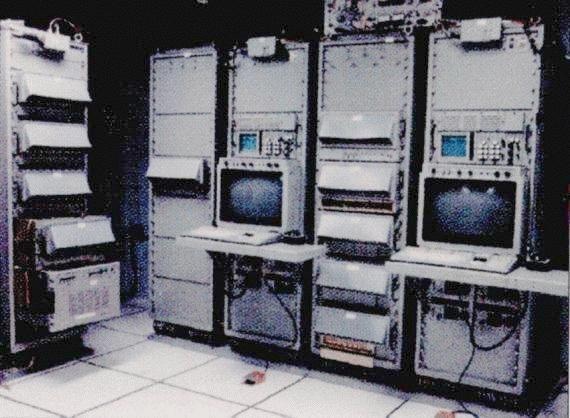

When I arrived at Lockheed Sanders in 1994, I was unusual: despite being a junior engineer, I had an active Top Secret/SCI clearance. This made me a cheap resource who could be put on our most secret and pricy projects. I was assigned to Combat DF and inherited the bugs the senior people didn’t want.

Almost immediately I received one that cracked me up. It was, roughly:

If you simultaneously push all the buttons above both workstations, the system will crash and reboot

If you imagine a CombatDF station inside a small compartment on a ship, you’ll immediately start wondering what kind of contortions would be needed to hit all of those buttons simultaneously. And who would think to do it? I knew. I knew immediately.

Bored kids on the midwatch. That’s who.

Weaponized boredom

Of the many things nobody tells you about the military is just how much time you will spend completely and totally bored. Part of why ships run drills all the time is that they fill time. Sure, they also contribute to the US Navy’s unprecendented level of training and damage control capability. Sweat in peace so you don’t bleed in war, and all that. But they also chew up time.

Want to run the “fire in missile upper level” drill on an SSBN? That’s nearly an entire 6 hour watch. 209 watch cycles left to go.

Fire in missile upper level is a great chance to truly become one with your Oxygen Breathing Aparatus. OBAs are a closed cycle rebreather that you use when fighting a fire on board a ship or submarine. USS Lafayette was a SSBN, a ballistic missile submarine, so she had 16 Poseiden submarine-launched ballistic missiles in her tubes. Any fire in a submarine is really bad. A fire in missile upper level had the potential to set off the conventional explosives in the W68 warheads, scattering radioactive and highly toxic materials all over the compartment. To practice this, we’d don OBAs, tape over 95% of the mask to simulate smoke, fight the fire, and then conduct decontamination, which we practiced by cleaning up talcum powder without disturbing it, getting in on your gear, or missing any. We all died. A lot.

But when you’re not conducting drills, there’s a high likelihood you’re bored. Your mind wanders and you start thinking — what would happen if I hit all of these buttons? Can I even hit all of them at once?

Fortunately, we’re a tool-using species, so coffee mugs, shoes, straight edges, and pens all become part of the solution. For me, it was the AN/BQR-21 station — more precisely, the two stations — and trying to flip all of them on both panels. It was possible, though it took two of us. We were a hole in the ocean, we were all bored, nothing on the screens but biologics. It didn’t fully crash, but it did glitch things for a bit on both panels. Nothing broken. If we had known how to submit a bug report, we would have.

It was an instantly recognizable bug, and a hilarious one to debug. I’ll leave as an exercise to the reader what kind of VAX Pascal coding decisions would lead to a limit on active buttons.

The risks of boredom stuck with me

The Navy’s approaches to boredom don’t really translate to the Real World (tm), but here’s the thing: engineering orgs have bored times, too. And I don’t mean “let’s all play Counter-Strike”-time. More the moments when smart but idle developers decide “I might need this data some day, so I’ll just set up a separate logging path to a different database” or “I was reading about Cassandra so I decided to add it our metrics system” or “I know A* was working perfectly, but I thought we could rebuild our world model for better monster pathfinding.”

The issue isn’t bright folks trying something new. Those are often spectacular moments. The boredom version has — in my experience — a more insidious problem, because there’s something about boredom that activates a teenager’s hyperrational thinking that will bypass normal thoughts about reliability, safety, and priorities. Worse, as we all know, once we start on weird side projects, the fun of them becomes an ongoing distraction, and we then rationalize both continued work and adding it to the priority list.

Suddenly, we’re risking the worst code you can ever produce: working code that you don’t need. Because working code that you don’t need is a compounding tax you pay forever.

Mission and A’s and O’s

So, I try to catch moments of boredom early and ensure we have a general back pressure against it. A clear mission and priorities helps everyone default to using time effectively. High transparency — even about hacks and side projects — helps prevent wild excursions into unnecessary areas while increasing the moments for knowledge collision and innovation. A’s and O’s and the 1/n rule are two of favorite approaches to this.

Don’t let boredom get weaponized against you.