the facebook mobile transition

Bruce and I joined Facebook in November of 2010, right after The Social Network was released. We joined as two of the dozen-ish Engineering Directors reporting to Shrep. Facebook had acquired our startup — Walletin — to bring in senior engineers who were proficient in javascript and client development. Why? Because Facebook was working on two mobile efforts that relied on high-performance javascript in the browser: a mobile version of Facebook’s platform that could run on mobile phones and the Facebook phone.

Farms and Feed

Although Facebook of 2010 was a largely desktop web experience, with a News Feed dominated by Zynga games, the iPhone was rapidly growing and it was clear to everyone that web usage on desktop was heading the way of the dinosaur. On the one hand, this was great for Facebook — Facebook itself is a far superior mobile product than desktop (sure, I have lots of friends who would take laptops to parties to post, but we’re a pretty nerdy group of friends.) It was obviously time to rethink News Feed, since anyone using it could see that an infinite series of nagging “click on my farm now!” notifications wasn’t good for Facebook.

But, Facebook Platform — and in particular, Facebook Game Platform — was valuable and it wasn’t clear how to make it run on mobile.

Hence, a mobile, HTML5 version of platform, aka Faceweb, Spartan; and, the phone project, aka Buffy, Slayer. Both wanted to bring the same social layer present in Facebook Platform to mobile. Both relied on javascript and web technology and needed skills that were oddly rare at Facebook.

This presented…challenges.

PHP

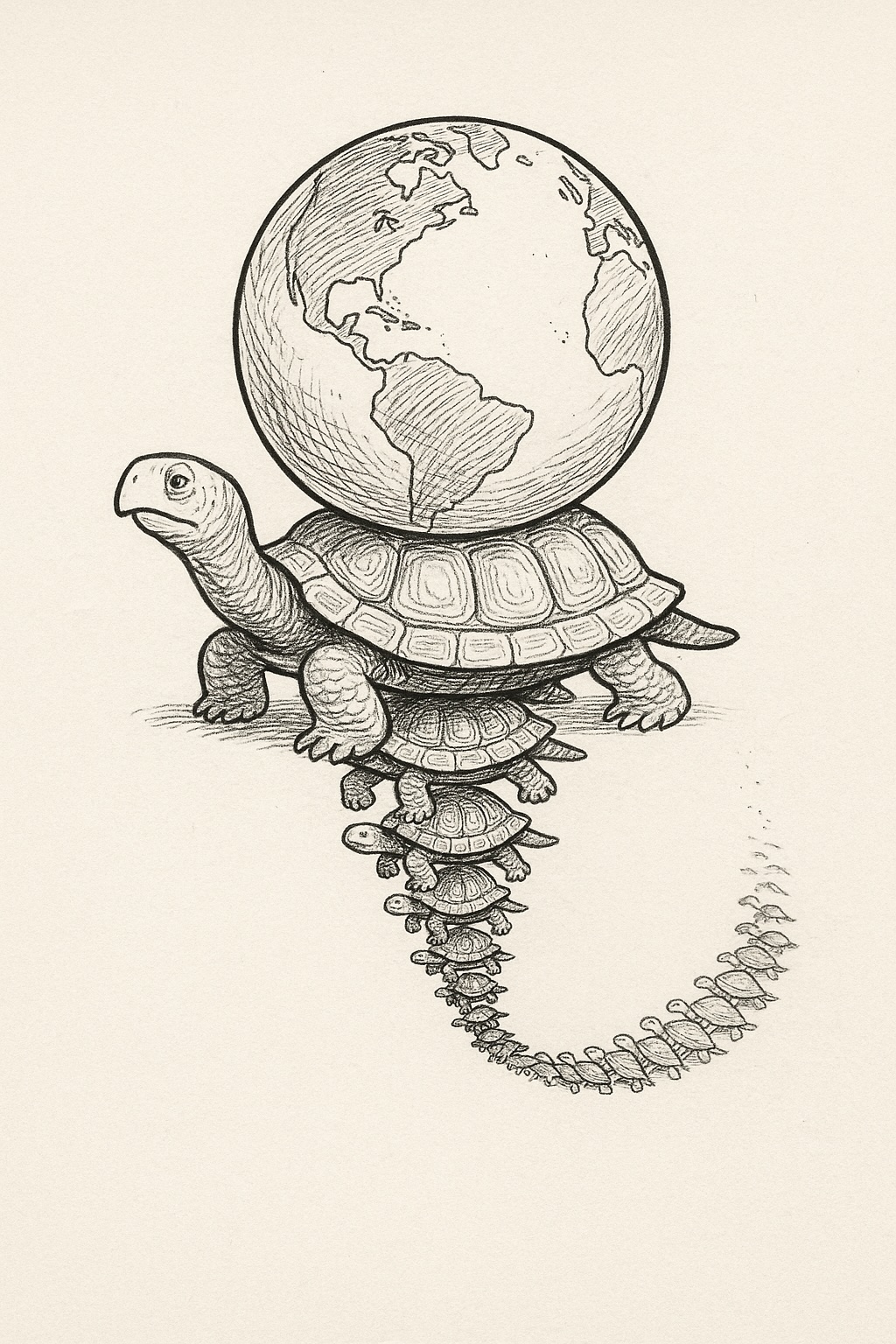

The brilliance of early Facebook — that nobody outside Facebook seemed to ever really understand — was that it was turtles all the way down.

And by turtles, I mean PHP.

In that era of Facebook, everything was PHP and URL. Want to hack on News Feed? feed.php is just sitting there. Photos? photos.php. Want to ship videos in a hackathon? Commit videos.php and show Mark the demo.

More than that, PHP meant anything you wanted to do was just a web push away (assuming you could get past chuckr’s push karma.) Want to ship? It’s a push. Rollback? Push that endpoint. Fix a bug? Push that endpoint.

PHP + Push meant nobody was moving as quickly or as flexibly as Facebook. There’s lots of writing about the Google+ launch lockdown, but what was less obvious was that every time Tech Crunch leaked something about G+ ahead of the launch, we’d start testing versions of the feature on Facebook within hours or days. There wasn’t a moment of doubt in engineering that Facebook would just run circles around G+.

Ironically, Google was the other suitor for Walletin, and I interviewed repeatedly for the Lead G+ role — which made sense coming off of Second Life. Unfortunately, one conversation with G+‘s leader at the time made it obvious he wasn’t actually conducting interviews and intended to Dick Cheney the process. Story for another day.

The lessons of PHP + Push

For all the (justified) attention “Move Fast and Break Things” gets, Mark’s push to shake up developer thinking was deeply tied to the benefits he had experienced learning to code web pages in PHP. Keep iterating. High information density on pages. Equally high conceptual splits across URLs.

Just keep writing code, just keep pushing.

And it worked spectacularly well. On desktop.

Rocks and snakes

So, Bruce and I landed on the game platform team. We released some cool javascript test code based on the Walletin code that abused browsers and got the Chrome team up in arms. Then in early 2011, Schrep tapped me on the shoulder and asked me to check in on the mobile team, maybe look at how their code was going, get a sense of whether things were on track.

I have an extremely high tolerance for ambiguity (Sundar’s pitch was “come to Google, poke around, find a way to be useful”) so that wasn’t a problem.

Well, it was a problem for some of the more tenured Facebookers. I like to make progress updates public and had a particular Facebooker take strong exception to my update of “continuing to kick over rocks, still finding snakes.” Were I doing it today, I’d try to be kinder — after all, it wasn’t this person’s fault that engineers had put on clown pants before coding FaceWeb or that Apple in that era was determined to keep mobile Safari hobbled. Plus, they’re a fancy CTO now.

Yeah, lots of rocks, lots of snakes. More than that, the reviews of our mobile app were continuing to get worse and worse. Facebook Mobile had gone through a few iterations since the iPhone launch, but it was always a separate team, always sort of chasing Facebook desktop. Of course, people wanted a mobile experience. Unfortunately, Faceweb just made things worse. It was slow, buggy, crashy, and of course still required Apple app store approval for releases.

First step, the safety shutdown

When teams get too stressed, tired, and pressured, they lose sight of how they got wedged in the first place. Soon after Schrep put me in charge of the mobile team, we had one of our typically disastrous releases and the team was scrambling to roll changes back and get an emergency version released through Apple. After we accomplished that, I just sent the team home.

I was super clear — you’re all ok, nobody is in trouble, but go home and get some sleep. Next week, we’re going to talk about the state of the app.

Here’s the thing: the team might have been inexperienced with iOS, but they were a brilliant group of Facebookers, and next week they came in with a very clear view we actually had a cultural challenge.

It was best summed up by a lunch discussion I observed between two Ivy League computer science PhDs. One was explaining to the other how they had completely figured out how to bypass Xcode and do everything with vim and command line tools. After a pause, the second engineer asked how they use the debugger. The first responded immediately: “Debugger? I just use lint!”

Coming from an embedded C background myself — arcade in particular was all assembly and C, often starting with a first step of “build a compiler for this chipset” — I couldn’t imagine a world without debugging and had rarely found value in lint. Conversely, programmers who’d maximized the learnings and advantages of scripting web languages — like PHP — approached things differently. Success on iPhone (and Android) was going to require a more compiled language mindset.

Buffy

A few months before, my unclear mandate from Schrep meant that I had found my way into the most secret project at Facebook: the Facebook Phone. A long-gestating project, the phone had started like doomed projects often do, in a too-clever deal (in this case, ATT, Intel, and Facebook.) As anyone who had worked on high performance and power-constrained computing in that era knew, Intel was really struggling and while they were desperate to get a piece of the new smartphone market, they were nowhere near having a viable (let alone competitive) chip. Shockingly, the project was really struggling.

A bright spot was the OS/UI. Like FaceWeb, it was envisioned as browser based — think mobile ChromeOS — which was a much better idea if you had the Android source code to work with. Schrep wanted it to move faster, so I picked up the phone front end in addition to the rest of mobile. It was a super interesting team — mostly ex-WebOS engineers who built similar concepts at Danger and Palm.

Sitting across both, it seemed like it might be a viable alternative to FaceWeb, though the state of mobile Safari was concerning.

The onsite, offsite

I have a playbook when there’s a big, ornery problem that lots of smart people are working on from different directions. It’s a playbook I learned from my friend Viktor at the unparalleled Rueschlikon conference:

- Identify the key thought leaders with different views on the topic

- Have them present their ideas as provocateurs, that is, from a strongly opinionated viewpoint and arguing for their position

- Treat the setting as a critique, namely that all ideas are to be debated robustly while remembering that we strongly respect each other

- No decision was to be made in the meeting

The topic was what to do about Facebook Mobile?. We constrained the question to iOS to help simplify the decision. We knew Android mattered and was growing, but we also knew that iOS was our priority in our largest markets. Our most engaged audiences were preferring iOS and the bar for quality there was much higher.

We examined three courses of action:

- Stay the course. Just keep digging into FaceWeb, use HTML5 as our path to a great mobile experience

- Leverage Buffy’s UI work. Take the more modern architecture of we were building for Buffy and use that

- Burn it all down, rebuild on native iOS

Most of the senior Facebook product engineering team was there in the room. Schrep attended as well.

It was an obvious, but not easy decision

It wasn’t even close. As anyone who was there can attest, it was obvious that rebuilding on native was the only viable solution. It really only presented two problems:

- We only had 3 really great, experienced iOS engineers at Facebook

- Mark had said — and done interviews — that FaceWeb was the future

Fortunately, career limiting decisions are sort of my thing, so first I pitched Schrep and then he told me to pitch Mark. To Mark’s huge credit, he didn’t fight the overwhelming data that we were going down the wrong path. Instead he simply asked how we were going to do it and how we could derisk such a big change.

It was November 2011. I told him he’d have a native News Feed to play with by March.

Git gud

Next problem: why did Facebook — one of the best places to work on the planet, a product-focused culture, and over 500 product engineers — have only 3 iOS engineers? Fortunately, Facebook had a mature, well-documented hiring process and it was easy to go diving through the reject pile.

Turns out, our process was filtering out iOS developers.

Standard Facebook Interview Question: “Design Facebook News Feed, including the backend”

iOS Developer Answer: “I don’t care about the backend”

Interview Notes: “1) TC does not understand basic Computer Science concepts. 2) TC has a bad attitude. Rejection!”

What was baffling to me was that we somehow were hiring Product Infrastructure Developers (Facebook’s second secret weapon after speed — that’s a post for another day), then called User Interface Engineers, led by Nan, and staffed with folks like Lee and tomo. I asked Nan how he managed to hire people like that given our hiring pipelines.

Turned out, he’d created a separate pipeline. Even better, he graciously offered to adapt his pipeline to iOS engineers. We turned our attention to Apple (and Apple alumni) and were able to rapidly start increasing our talent base.

We also knew we’d need to broadly adapt as an engineering culture. Mike had just joined us and immediately brought two key innovations: regular, date-driven releases and broad native training. Facebook Mobile had historically been a lot like high fashion with seasonal releases. At one point, we even found a meme on a public meme site clearly made by an Apple app store reviewer “Facebook Mobile submitted again, wonder if they’ll pass?” Mike convinced me that fixed-date releases — starting at every 2 months, then getting faster and faster, would be the best path to fix our development process.

I agreed and got Mark to agree. Mark had a brief moment of “but I can just release what I want whenever, right?” but rapidly agreed that fixed dates were worth the small risk of a feature he really wanted getting delayed. To his huge credit, he respected that agreement even when we missed something he cared about.

Mike also brought in Big Nerd Ranch and we let anyone — from developers to PMs to recruiters — take iOS and Android training. We put hundreds and hundreds of engineers through it and rapidly expanded awareness of what it meant to deliver compiled code. We also learned that a lot of our Infrastructure engineers were super excited to work on native product development, a wonderful and unexpected resource.

A different product, too

It was time for another career limiting meeting. Mark had been pushing “mobile first” from long before I joined — the stories of “Facebook missed mobile” were always missing the point. Mark saw mobile as early as anyone. Unfortunately, when an organization doesn’t have the capacity or capability to execute on the CEO’s vision, bad things happen. In the case of Facebook, it meant facing the constant cognitive dissonance of being a very product-focused engineering org but shipping a product that hundreds of millions of people relied on but we all knew was buggy and terrible. Worse, when the CEO keeps saying “mobile first” but nothing changes, people start ignoring the CEO.

Mick and I came up with a new framing: “mobile only.” We looked at the curves and any way you looked at them, it was really clear that within a very short period of time, desktop web would be the legacy product, that the vast majority of usage and growth would be on mobile. I then went to Mark and pitched him on the new framing. I also pointed out that because he was a very involved leader (Eye of Sauron was often invoked for what Mark was paying attention to) his lack of modern mobile instincts were slowing us down. If we really wanted to get great at mobile, he needed to really understand the transition. What it meant for development, shipping, design, etc. So I pitched him on weekly Mobile 101 sessions.

Again, to Mark’s credit, he agreed. He took it seriously, made the time, and like anything he throws himself into, within weeks was deep enough to be asking questions that stumped the rest of us. He rapidly made the kind of change only a CEO can make: any design review that didn’t start with mobile mocks was immediately ended. You don’t have to get thrown out of the fishbowl too many times to adjust your behavior and very quickly everything shifted.

Creating the modern feed

Of course, none of this would have mattered if the native code didn’t move forward. Mick and I rethought how News Feed would behave in a performance mobile environment, the team moved quickly, and as promised in March Mark was playing with a News Feed that loaded instantly, you could infinitely scroll as fast as you could swipe, and was stutter-free.

It was amazing.

At the time, we’d been really struggling with the monetization angle. It’s hard to remember, but at this time, News Feed only had social content in it. Ads existed in the sidebar ads section on desktop and in the top bar on mobile. We’d been debating changing the rules with Mark for a while — early experiments with app install ads, for example, showed that we could connect the ad click to the mobile app installation, which seemed pretty valuable! — but Mark had wanted News Feed to remain purely social.

Using the new iOS app and seeing how quickly you could scroll, he changed his mind and in March of 2012 we walked out of a meeting with permission to explore what would become the News Feed — and really the prototype for every attention-reinforced feed on the planet. (My feelings about the impact of that is a story for another day)

When we knew

Within weeks, we knew what we had. Thanks to the asking-for-forgiveness-not-permission of Michael, we had deployed an experimental, paid mobile News Feed product called “Sponsored People You Might Like” that took off like a rocket. App install ads followed, despite an attempt to kill them by a thankfully rare turf war by another long-tenured Facebooker.

I had picked up Boz as a report as he bounced between jobs and after we built out a new thesis on mobile advertising that led to my third career limiting meeting — when I went in and convinced Sheryl that her ads strategy was about to be out of date and she should bet on Boz instead. She did and that worked out pretty well.

Getting the data out to the edge

Things were going remarkably smoothly. We were pushing towards the IPO and Bret was handing all of mobile over to me because he had other ideas post-IPO. There was really only one big challenge left — with a high performance mobile product, how do we turn all of Facebook into an API?

Nowhere captured the PHP + push mentality quite like the notification beepers on mobile. While debugging why the beepers were wrong, we noticed that the javascript for the beepers was receiving and parsing markup, rather than JSON. That’s weird, we thought. Turns out, markup was being stored in MySQL and sent to the mobile client as data. As Schrep would say, not ideal.

So, I did what any reasonable manager would do in this situation. I turned to Lee, Tomo, Schrock, and Jackson and gave them the requirement. Two weeks later, Schrock demoed what would become GraphQL. Not only was it amazing, because of PHP’s flexibility, they’d already figured out a way to infect basically all of Facebook’s systems with it and turn any URL endpoint into an API.

edit on 15 July 2025: Jackson doesn’t remmeber being at the “how the hell do we do this?” conversation, though he was there at Schrock’s first, mind-blowing demo and an early consumer of GraphQL.

We had our data. We briefly had a bug that doubled the load on all of Facebook’s servers — that wasn’t the best day — but we had our solution!

The rest of the way

We had our “botched” IPO and got to watch the stock go down to $17, but we knew we had mobile solved. We released the new iOS app to rave reviews. Mark gave me a bonus and we talked about next steps for me at Facebook. I made the incredibly stupid decision not to commit to staying for at least four more years because 2012 me was pretty stubborn and unhappy. Dumb.

Mark and I did an all hands after launching the new iOS app and acquiring Instagram that showed just how much we’d transformed the quality and engagement. We showed mobile revenue curves. I tried and failed to get a large roomful of people to stand up to in order to recognize that everyone had been part of this transition, but it was true. It’s hard to capture how many people had been part of this change.

(We knew because along with everything else, Mick had a weekly internal post bragging about everyone who helped.)

Android followed quickly after, too. Before long — as predicted — mobile was the majority of usage, growth, and revenue. Every team at Facebook was directly contributing to mobile and I was excited to be able to eliminate the mobile team. You can’t have a specialized team when the whole company is working on something and that final wind down was the endcap on the transition.

In a little over a year, we’d gone from completely broken mobile products, unhappy users, and basically no revenue to the best and largest mobile products in the world. Not too shabby. Maybe you could argue Satya’s transition to Cloud was a bigger, more important pivot. Or Andy Grove’s DRAM to CPU pivot.

But I think what we did was pretty amazing.

But what about Buffy?

That’s a story for another day.