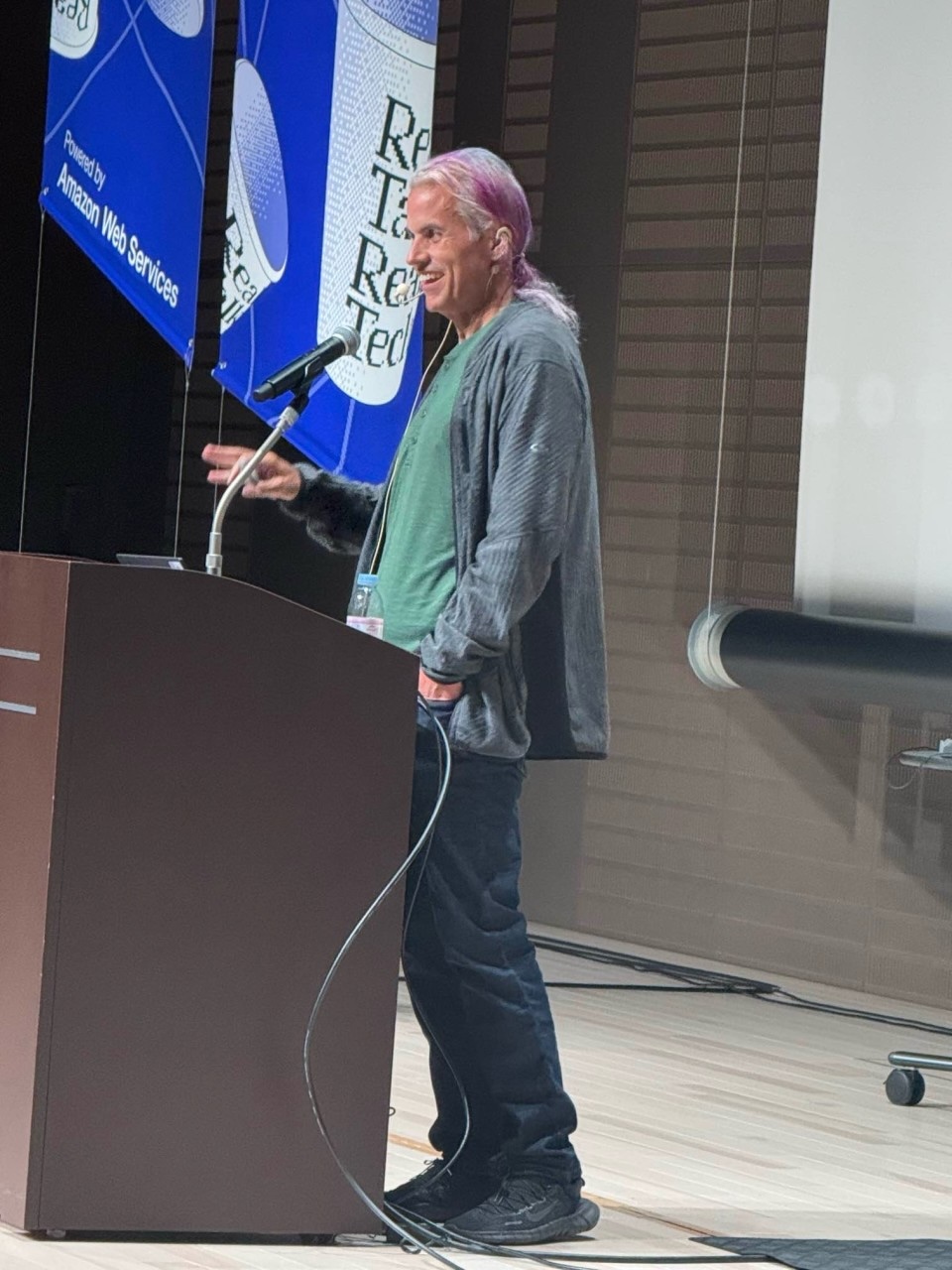

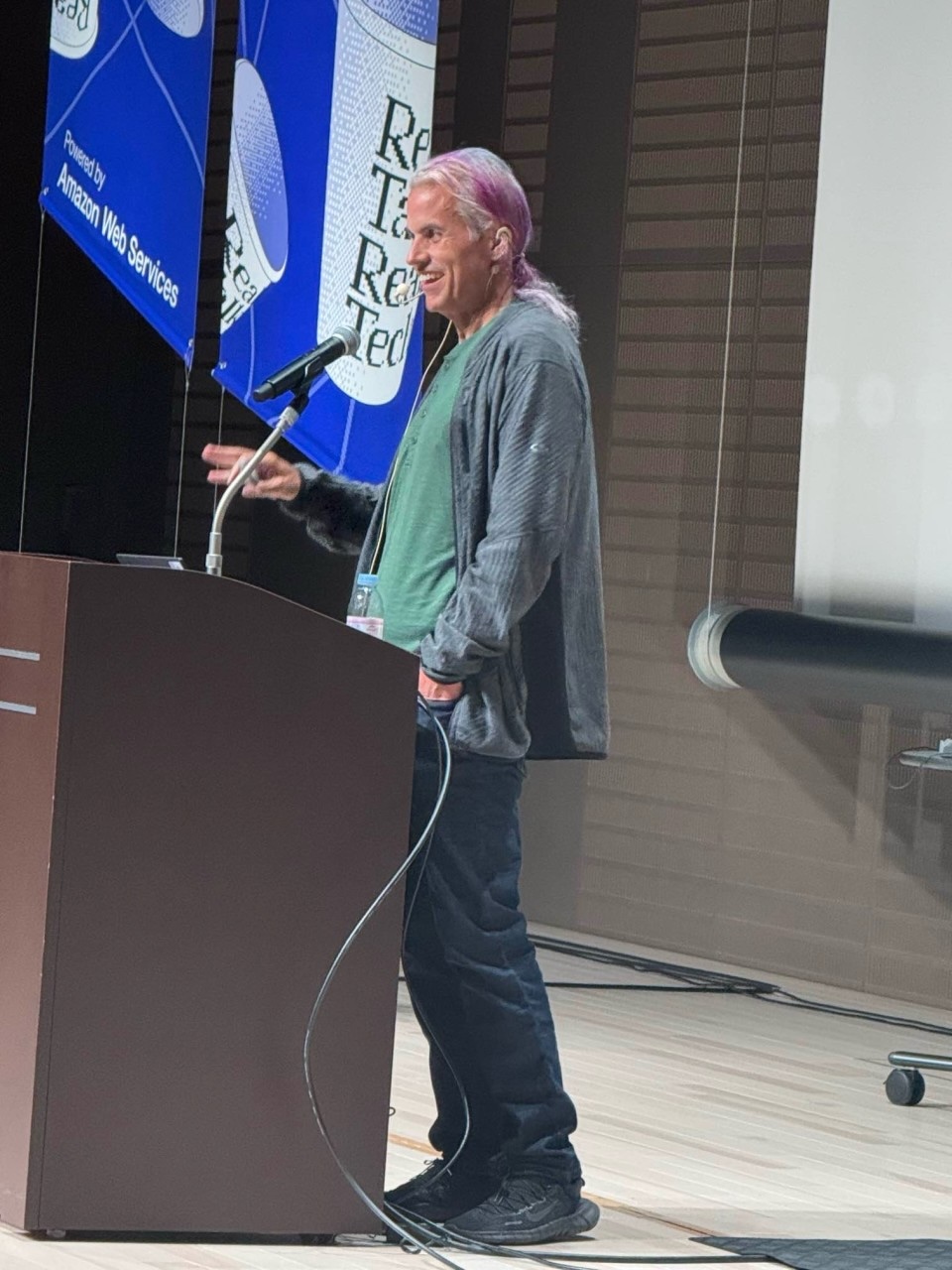

Apparently it’s CTO week in the technosphere. I just gave a keynote at the AWS CTO Night and Day conference in Nagoya. A “Why I code as a CTO”-post got ravaged on Hacker News via incandescent Nerd Rage. Then there was some LinkedIn discussion about “how to become a CTO”-posts, and how they tend to be written by people who’ve never been in the role. My framing is that being a CTO is generally about delivering the impossible — if your job was easy, your CEO would have already hired somebody cheaper.

Like with planning, these are tricky discussions to navigate because a) nobody really agrees on what the hell a CTO is and b) even if we did, it’s so company — and company stage — dependent that the agreement would be an illusion. The CTO role has only really been in existence for 40 years, so it isn’t shocking that defining it can prove challenging.

AWS asked me to weigh in anyway, so let’s give it a go.

But first, a brief incentive digression

Incentives. A CTO title from a high-flying company can be the springboard to future funding, board seats, C-level roles elsewhere, and all kinds of Life on Easy Mode opportunities. It can make you Internet Famous (tm), lead to embarrassingly high-paying speaking engagements, invitations to lucrative carry deals as a VC, and get you on speed dial from journalists at The Information looking for inside information.

For the non-business, non-CEO founder, CTO is a weighty title that implies a certain balance in power and responsibilities1. During fundraising, the CTO role can help early stage companies look more grown up2, signal weight of experience, level of technical moat, etc. All good.

A developer might also have grown up thinking about CTO as the gold ring they’re aspiring to.

These are all perfectly reasonable career. There are similar incentives around being a CEO. Pretending they don’t exist is foolish, but after acknowledging them, I want to focus instead on what matters for technology companies and organizations.

Building the right way

As CTO, you are one of the few leaders well positioned to own how you are build, prioritize, and allocate technical resources. In particular, are you chasing a well-understood product/problem/goal or are you venturing boldly into terra incognita? This distinction matters, because the tools for the former — hill-climbing, metrics-driven OKRs and KPIs — are much more challenging (and sometimes actively destructive) when applied to the unknown. Similarly, highly unstructured R&D adventures aren’t the most efficient or effective way to deliver a well-understood product. Neither is better in all cases and (almost) no company is wholly one or the other, but as CTO you must be opinionated here.

Learning and rate of positive change

I’ve written about this elsewhere but how fast you learn and measuring your rate of positive change delivered to customers is on the CTO.

My favorite rule of thumb from Linden Lab: 1/n is a pretty good confidence estimate when judging an developer’s time estimate in weeks.

Stay in the Goldilocks zone

In astronomy, there’s the idea of the Goldilocks zone. It’s the distance from a star where water is liquid. Too close, everything boils off. Too far, everything freezes. CTOs (like product/tech CEOs) have a very similar tightrope to walk. Stay too close to the tech, too close to all the critical decisions, and you deprive your company and teams from the chance to grow as leaders and technologists. Suddenly you’re trying to lead weak, disempowered leaders through a micro-management hellscape. On the other hand, drift too far away and your team — and CEO — loses a critical voice and thought partner. You’ll find yourself guessing and actively misdirecting the technology direction because you’re out of the loop.

What’s the right balance? It depends. On scale, on your skills, level of technical risk around you, etc. It’s also not static. Take a week to go through engineer onboarding. Challenge a deputy to deeply explore emerging tech. Explore the tech decisions that are being routed around you.

Two full time jobs

At any stage, a company that is dependent on technology innovation and delivery has distinct — but equally critical — challenges to solve: org health and tech vision.

Org health. Can developers able to do their best work? Are they setup for success? Are there minimal impediments to doing great work? Are they able to hire and fire effectively? Are speed and experimentation properly balanced against risk and debt? How does the tech org fit into the company, cooperate with other orgs? Do developers and other tech employees have career paths? Are ladders, levels, and comp aligned with company principles? Is the culture working?

Tech vision. Is the company looking around technology corners? Are the deeply technical decisions correct, tested, and working? Is the tech org staffed to solve both the current and next set of technology problems? Is the technology vision correct? Is the tech organization delivering against company mission, vision, and goals? For most people, one of these two challenges is likely to be more exciting and interesting. My past mistakes as CEO or CTO have been on the org health side. I’m an introvert with a great act, so I’ve learned to seek out strong partnership to reduce that risk.

Sometimes early stage companies can split this across CEO and CTO, or two tech cofounders can split it up. No matter how you solve it, recognize that you do need to solve it.

There are even options where the CTO has neither of these responsibilities, which can also work so long as somebody does have them.

Don’t just import hyperscaler crap

Real Talk (tm): you probably aren’t a hyperscaler. I hope you get there, but you’re not there yet. All those fancy toys Google, Meta, et al brag about? They solve problems you probably don’t have yet. Worse, they often generate high fixed costs/loads that hyperscalers don’t care about but will materially impact your business.

A few last thoughts

I’ve known quite a few extremely successful CTOs and if there’s one commonality it’s how differently they approached their role and day-to-day activities. Several wrote code everyday. One acted more as a private CEO R&D lab than org leader. Another was 85% VPE but had the keenest sense for emerging tech I’ve ever seen. Yet another was mostly outbound and deal focused3.

All of them rocked.

So, think about the core of the job that your company needs, is compatible with your CEO’s style, and fits your skills. Figure out how to really know how your team and company are performing. Rinse and repeat.